Paddington’s Contribution to the War Effort

Celina Fox has been digging into the archives and has come up with a fascinating account of the great project for the removal of our railings during the Second World War, to say nothing of the farming of 700 pigs at the Paddington Rec and unruly scenes at its, pigless, post-war reopening.

During the Second World War, the Paddington Mercury covered the local stories typical of a busy metropolitan borough – murders, suicides, traffic accidents, appeals for funds to buy Spitfires and bombers, to support the Red Cross or refugees from the Continent and, from September 1940, to relieve the distress of London’s air raid victims. There were frequent reports of looting from bombed houses, summons for breaking the blackout as well as for keeping disorderly houses, particularly on the Paddington Estate. There was a chronic shortage of air-raid shelters. The newspaper also featured the Borough’s response to the national salvage appeal, encompassing paper, rags, meat bones and metal.

The Ministry of Supply had established an Iron and Steel Control at the start of the war but as scrap metal from abroad was still available, at first no attempt was made to check civilian demand. It was only in the summer of 1940, when overseas supplies were severely threatened, that the relevant Minister, Herbert Morrison, appealed for more salvage. The Mercury reported on 3 August that the Women’s Voluntary Service had started a giant canvassing campaign in response. Paddington was divided into salvage districts, each with a dump – the first established at the Lock Hospital, Harrow Road. The minutes of the Borough’s Works Committee stated that, with the approval of the Emergency Committee, 138 iron guard-posts were being removed for utilization for war purposes, together with the dog rails in St Mary’s churchyard. Furthermore, in cooperation with the Paddington Estate Trustees and other private residents, a quantity of privately owned iron railings had been dismantled.

These measures were taken on a voluntary ‘goodwill’ basis, which the Borough strongly endorsed. On 15 February 1941 the Mercury featured ‘Paddington’s New Salvage Scheme’ to rope in schoolchildren as salvage collectors and boasted that during the past year Paddington Cleansing Department had handled over 1,500 tons of salvage, valued at some £4,400. The Council also branched out into the pig-farming business, starting piggeries at Mill Hill and subsequently at Paddington Recreation Ground. In April the Queen paid a special visit to Paddington to tour of the Borough’s salvage depots at 115 Westbourne Grove, 10 Clifton Road and 634 Harrow Road, before inspecting the main collecting and sorting depot on North Wharf Road, where she was shown the arrangements made for loading the sorted salvage into barges.

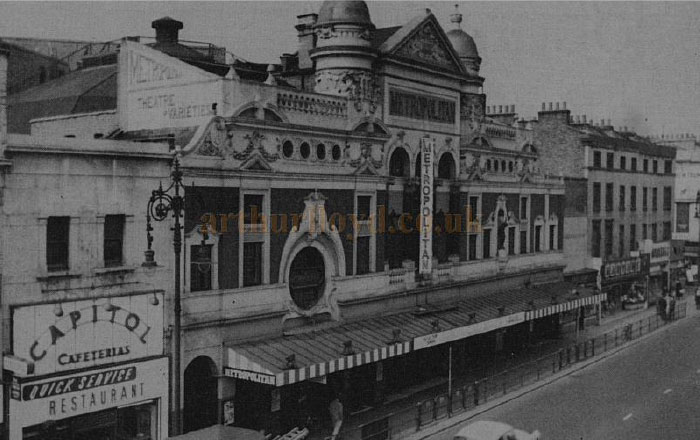

Increasing pressure was put on private landlords who were reluctant to contribute iron railings, given the amount of scrap still conspicuously lying about uncollected and the anticipated effect their removal would have on property values, at least prior to the introduction of compulsory powers. In April 1941 the Borough’s Works Committee was informed that the Ministry of Supply had drawn attention to the shortage ‘of the particular type of scrap metal which may be obtained from railings and which had a special value in the manufacture of ships’ cables, chains and other fittings.’ As no equivalent weight was so valuable, the Ministry invited the cooperation of councils in securing an increased supply. The Committee gave directions for the Ministry’s request to be communicated to owners and occupiers of premises or open spaces where railings existed, asking them to permit the Council to remove the railings for surrender to the Ministry. In September a further salvage drive commenced with a mass military and civil defence parade from the Town Hall (then on Paddington Green but subsequently demolished in the 1960s for the construction of Westway) to Paddington Recreation Ground accompanied by bands, sporting events, a fire-fighting demonstration and community singing by schoolchildren.

On 4 October, the Mercury printed a notice signed by the Town Clerk, headed ‘Metropolitan Borough of Paddington, Removal of Railings’. It announced that following a direction of the Minister of Supply, the Council intended forthwith to carry out a survey and make a schedule of ‘unnecessary railings, gates, posts, chains, bollards and similar articles in the Borough’, all of which would be removed by the Ministry for war purposes. However, the notice added, it was not intended that railings maintained for safety reasons and those of special artistic merit or of historic interest should be included in the schedule, and any owner claiming that his railings came within these categories had to deliver his appeal to the Town Hall not later than 10 am on Wednesday 15 October, against the inclusion of such railings in the schedule.

In the few days allotted, Paddington freeholders must have got their skates on to appeal, not on artistic or historic grounds – Victorian railings were regarded, at the time, to be of little aesthetic interest – but for safety reasons. As was the case all over London, the removal of area railings guarding basement areas would have been lethal in the blackout. On 24 January 1942, the Mercury announced that the removal of railings by contractors was proceeding – in fact, prior to statutory authority to requisition which only came into force in March 1942, delayed by the dilatory return of some local authority schedules as well as difficulties over landlords’ and tenants’ rights and levels of compensation. Meanwhile, a Ministry of Works official used the Mercury to alert its readers to the national necessity to collect railings. It was one of those unpalatable war measures, like food-rationing and the black-out, which had to be endured. Steel was the sinews of war, he declared, citing an impressive list of those who had already sacrificed their railings on the national altar – Buckingham Palace, London parks, squares and churches, the Mansion House, College of Arms, Sion College and Temple Gardens. It was now the turn of the private householder whose important addition to war effort would reappear as guns, tanks and ships to protect the whole country.

Under the headline ‘Your Railings Will Keep Hitler Out’, on 21 March 1942 the Mercury reported that London was yielding over 5,000 tons of scrap-metal a week from the salvage of iron railings and gates and that more than 40,000 tons had already been collected. However, owners asked why the railings were not being cut with a hacksaw or burnt with oxy-acetylene, instead of being smashed with heavy sledge-hammers, thereby inflicting damage on boundary walls. Such complaints were vigorously countered. It was pointed out that in London alone, railings were being taken from 45,000 properties a week and sufficient hacksaws were simply not available. Oxyacetylene was used to burn through wrought-iron railings but not cast-iron ones, which needed too much oxygen and its supply and transport were in short supply. The public must realize that time, money and skilled labour were not available to cut every rail and extract every gate post without causing damage. Where brickwork or stonework was damaged, contractors were instructed to make good as far as supplies of material and labour allowed but, the Ministry emphasized, it was a national emergency. By 18 April 1842, the Mercury could announce, under the headline ‘Iron Railings Hit Back at the Enemy’, that according to figures just published, Paddington had contributed 1885 tons 16 cwts, and that a ton of scrap equalled 150 shell cases for eighteen-pounder guns.

The results of the removal of railings in the Second World War can now barely be traced in the streets of the old Metropolitan Borough of Paddington covered by the Paddington Waterways and Maida Vale Society. The fact that houses along the major avenues and crescents were part protected with stucco balusters and part by railings safeguarding basement areas ensured that these original Victorian fittings remained in place. But stretches of front garden were deprived of their boundaries, as can be seen in locations where the stumps of the original ironwork in the stone or brickwork base are visible (for example, at 25-26 Maida Avenue), despite later replacement with hedging, fencing or new railings of varying design and quality.

As for communal spaces, our area was again in part protected because many gardens were enclosed behind houses rather than being squares in front of properties, surrounded by roads and enclosed by railings, as was the case on earlier London estates. The major exception was Paddington Recreation Ground, the boundary railings of which were removed in 1941. Paddington’s resulting contribution to the ‘National Larder’, as the Mercury expressed it on 5 August 1944, was also a source of some pride. Its herd of thirty pigs had grown to a thousand (700 at the Recreation Ground, 310 at Mill Hill), worth £10,000. Despite the slaughter of the entire stock in 1942 through swine fever, since 1940 it had provided the nation with 800,000 lbs of pork meat – the largest municipal undertaking of its kind in the country.

To the relief no doubt of neighbouring residents, Paddington’s piggeries did not outlast the war. In a report of the Recreation Ground’s Committee of Management, dated 2 July 1945, it was revealed that the Ground was suffering from the blight suffered by many London parks, squares and gardens opened up to the public by the removal of railings: ‘great difficulty had been experienced in preventing unauthorized entry at night, theft and wilful destruction of Council’s property, and annoyance by certain unruly elements.’ An ambitious £80,000 plan had been drawn up to redevelop the Ground with an array of sports’ and childrens’ play facilities but an essential preliminary was the provision of new railings to close the Ground at night. In May 1946 the Council approved their reinstatement and the following month permission was obtained from the Ministry of Health to obtain the steel required. Prior to the invitation by the Borough Engineer of tenders, it was arranged for the architect of the redevelopment scheme, Edward Prentice Mawson, to approve the type of railing to be erected to harmonise with his proposals. Tenders were received on 30 September and the lowest from Hill & Smith Ltd of Brierley Hill, Staffordshire, amounting to £1,498 14s 6d, was accepted. The final cost rose to £1,849, owing to an additional eight tons of steel required, making thirty-three tons in all, but this still seems a bargain – by the time St James’s Square (a fifth of the then size of the Ground) managed to replace its railings in 1973, the cost was £23,000.

On 8 May 1948 Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein opened the restored Paddington Recreation Ground, covering more than thirteen acres. He arrived in his famous car, ‘Old Faithful’, used in the African and European campaigns, having driven through the borough – along Blomfield Road, Warwick Avenue, Castellain Road and Morshead Road. A guard of honour was provided by local branches of British Legion and incidental music played by Royal Marines band. After speeches, Lord Montgomery cut the tape across the entrance to the children’s new play area, and at a flag signal given by a Boy Scout, two cricket matches, bowls matches, tennis matches and an inter-school netball match commenced simultaneously. There was also an athletic and sports meeting in the track enclosure. In the evening a concert was given by the Great Western Railway Staff Band.

Unfortunately, the Mercury edition of 29 May 1948 led with the banner headline, ‘Vandals Havoc at Pleasure Ground’. Councillors had learnt that as well as having to foot £500 for the opening ceremony an additional £449 of damage was caused by crowds on the opening day – to the marquees, rockery, flower beds, privet borders and young trees, as well as by broken bottles thrown into the paddling pool. The Parks and Cemeteries Committee mulled over the problem and concluded it was caused less by the breeding of hooligans in the Borough than by carelessness, though it was disappointing that the grownups had made no attempt to prevent it. They would try to get the co-operation of the parents to make their children respect other people’s houses and property. Post-war hopes were high for a better world to come.