The reasons why the word Metropole or Metropolitan appears in the names of buildings by the Edgware Road flyover go back across the last two centuries…

The reasons why the word Metropole or Metropolitan appears in the names of buildings by the Edgware Road flyover go back across the last two centuries. It harks back to fun, boozy camaraderie, and the days when music halls, and the Metropolitan in particular, were the fun palaces of their time. Christopher Cook here provides the history and some memories of his visits from the days when just a lad.

If there’s one thing that is sadder than a lost theatre, it’s a theatre that’s being pulled down. With the roof off, the seats torn out and the balconies half gone who would believe that this was once a place of escape, of make believe and theatre magic? There’s a photograph taken on September 20th 1963 and published in the old London Illustrated News of the Metropolitan Music Hall on its last legs. In the foreground a pair of the handsome cast iron pillars that supported the interior are heaped up like broken limbs while at the back of the photo the balcony and the gallery are on their last legs. The theatre architect Frank Matcham’s grand old lady of Edgware Road is about to take her last curtain call.

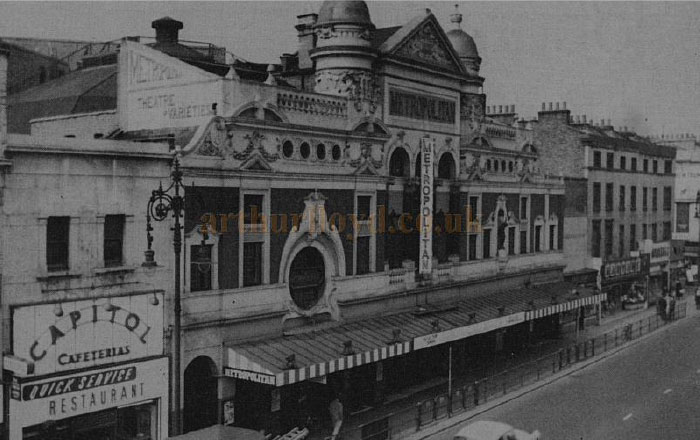

I remember looking at the theatre with its faintly Indian twin domed towers on either side of an imposing pediment from the top of the 16 bus as my grandmother, who lived off George Street, took me up to Maida Vale for tea with a nattering old friend. (They were both very Irish). And I also recall an evening in the theatre, an ‘Irish evening’ as I remember it, with theatrical colleens in fetching emerald green satin. I think they were more the Tiller Girls than Michael Flatley’s hoppers and skippers but maybe I am wrong. And did the comic have a shillelagh? I am more certain about the electrical numbers on either side of the stage that told us which act we were watching. I must have been about 12 years old and I suppose that the theatre was already a bit down at heel, but my strongest memory is of plush and comfort, and knowing that it was an infinitely more exciting place than the world beyond the foyer.

The Metropolitan had excited audiences from Paddington and beyond for over 120 years. Once there was a pub on the site, the White Lion rebuilt in 1836 as Turnham’s Grand Concert Hall, just in time to entertain the men who were building Brunel’s Great Western Railway. A quarter of a century later it was turned into an altogether grander building at a cost of £25,000 and with seats for 2000. But it didn’t become the Metropolitan Music Hall until 1864 and before long it was just the ‘Met’ and home to a generation of High Victorian popular entertainers.

In April 1896 the demolition men took to the stage and on the 17th August 1897 the foundation stone was laid for a brand new theatre, to be designed by Frank Matcham, perhaps the greatest theatre architect of his day. (Matcham’s masterpiece, the London Coliseum, home now to English National Opera was gloriously restored a few years back.) With fifty three theatres and music halls to his credit Matcham was already a veteran when he began work on his Met, which was to be bigger and much better than its predecessors. Paddington was going up in the world. As one newspaper reported it, “The nobility and gentry of Paddington are well cared for in the matter of entertainment, and the Met, as their local variety temple is called, has for many years applied the discoeuvrement (sic) so necessary to every class of the dwellers in this great metropolis. The neighbourhood, however, has very much extended since the hall was first established, and for some time it has been felt by Mr Henri Gros, the latest proprietor of the Edgware-road establishment, that his property needed reconstruction.”

Reconstruction meant an enlarged stage, improved dressing rooms and a new facade facing Edgware Road and all within the footstep of the original building. The balcony and gallery were to be ‘built on the cantilever principle’ so there’d be no pillars to restrict views and on either side of the stalls there would be white marble private boxes. This was indeed a ‘palace of varieties’ with a capacity of nearly 3000. How blessed were the nobility and gentry of Paddington, and even more so the ordinary men and women of the neighbourhood as they luxuriated in the new auditorium decked out in a Flemish style having made their way into the theatre through a white marble foyer ‘surmounted by Indian ornamentation in rich colours’. As at the Coliseum Matcham seems to have turned the British Empire into theatre.

But Frank Matcham was an eclectic borrower. So as the wide-eyed local reporter who was present at the opening night on December 22nd 1897 told his readers, ” Of the two saloons for the convenience and refreshment of the ground-floor occupants, one is charmingly decorated in Burmantoft faience, and the other in walnut panelling, with alternate mirrors and tapestry of an original decorative character, the ceiling being treated in the style of Louis XVI.”

And what of the performers on offer in a theatre that was not lit by gas but right up to date electricity? Their names are almost as dim to us now as that of Mr Harry Smith of Garrick Street who had installed the electrical equipment? Tom White and his Arabs, Princess Pauline, Miss Cora Cardigan, Miss Alexandra Dagmar, Mr G. W. Hunter, Mr Harry Atkinson, the Dumond Parisian Minstrels and etc belong to a world of entertainment that has completely disappeared. And when we fast forward to the 1930s and 40s the entertainers still seem to be ghosts from a forgotten theatre world that was vanquished by television. Alfred Thripp, ‘The Popular BBC Blind Vocalist and Pianist’ or the ventriloquist Chas Hague ‘Two Heads with a Single Mind’. Mind you Max Miller appeared on the same bill, and ‘the Cheeky Chappie’ has never gone away. At least in the form of the loud suits and the battered trilby.

What finally did for the Met wasn’t just the growing popularity of television. It was the Metropolitan Police who, having lost Paddington Green Police Station under the new Marylebone flyover, bought the music hall which was then struggling on as a wrestling hall and built a new station on the site. So the Met is buried under the Met’s concrete fortress by the flyover.

Before they pulled down Matcham’s theatre there was one last musical hall night. It was Good Friday, April 12, 1963 and the all-star bill, compered by Tommy Trinder, included Hetty King, Issy Bonn and Ida Barr from the old days, and in contrast Johnny Lockwood, Mrs Shufflewick, Dickie Valentine and Ted Ray. They were turning them away as the curtain went up at the Metropolitan Music Hall for the last time.